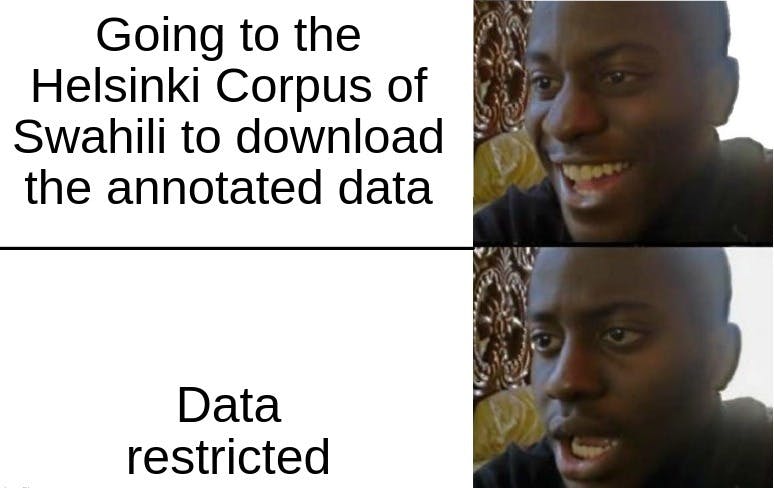

In an endeavour to better understand part-of-speech tag in Swahili, after reading Peter W. Wagacha, Guy De Pauw 1, and Gilles-Maurice de Schryvers Data-Driven Part-of-Speech Tagging of Kiswahili paper. Intrigued by the recommendation to look at the morphological analysis when creating part of speech tags in Swahili led me to the annotated Helsinki Corpus of Swahili. The enthusiasm I had vanished when I learned the data was restricted.

According to the Helsinki Corpus of Swahili, there are two ways of accessing the data; One, I had to have an academic status in an institute belonging to the Haka or eduGAIN federation in which most African Universities were not members state. Two, I had to apply for personal access rights which required me to have an email linked to a University; unfortunately, I did not fit the above criteria due to my graduate status and being an independent researcher.

Further data searching, I came across Kencorpus, A Kenyan Language Corpus of Swahili, Dholuo, and Luhya for Natural Language Processing tasks. My interest was the part-of-speech tag. Though they did not touch much on the part-of-speech tag in Swahili, they referenced an existing work done by the Helsinki Corpus of Swahili. I commend and appreciate the part-of-speech tagging done on Dholuo and Luhya; their contribution to such languages will spearhead research in other Kenyan local languages. A more desirable solution is needed to address the lack of tools to do part-of-speech tags in Swahili, which are open source and available to anyone across the globe.

Out of curiosity by the success of GPT4 and its design architecture on large language models. I tried sourcing Swahili datasets created for language models. Datasets such as the cc100-Swahili Dataset created by Conneau & Wenzek et al. in 2020 and Shivachi Casper Shikal & Mokhosi Refuoe show a promising start. When compared to languages such as English, the data is less and limited. Due to data inadequacy, Swahili become a low-resource language.

It got me thinking about why there are fewer publicly available datasets, yet Swahili has more than 200 million speakers. According to Piedmont Global Language Solutions, countries such as the USA has more than 90,000 Swahili speakers, which will continue to grow in the coming years. Last year, UNESCO declared the 7th of July each year as World Kiswahili Language Day, becoming the first African language to have such status. There is a need to create awareness of the importance of Swahili as a language of interest in Africa.

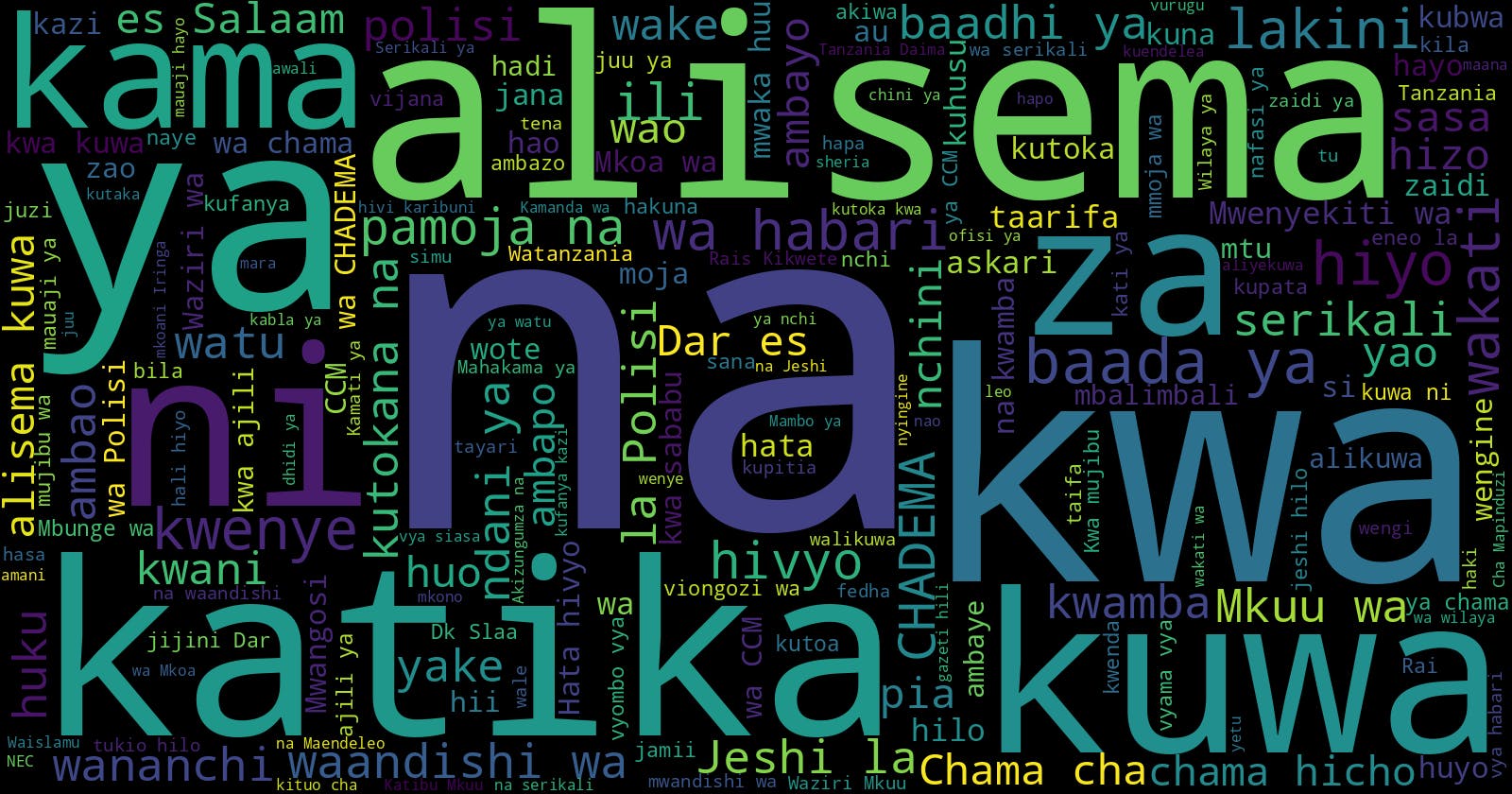

There are a dozen Swahili data in East Africa. The print media contains records of Swahili news articles and conversations. So there is a need for our government, university, and research institution to come up with better strategies and policies that support data collection processes and research. We cannot jump into the iceberg trying to solve the issue of local languages when we have not succeeded in conquering Swahili in tech space.